For a happy marriage, it is necessary, of course, that the engaged couple find each other congenial and enjoy each other’s company.

For a happy marriage, it is necessary, of course, that the engaged couple find each other congenial and enjoy each other’s company.

They must agree to share loyally the joys and the sorrows of wedded union and fulfill its obligations.

Each one must be bent on procuring for the other as much happiness as possible and oblige himself beforehand to a mode of life which will disturb his partner as little as possible.

The husband must love his profession, and his wife should share this love or at least neglect nothing in order to respect and facilitate it.

They should be able to make their decisions together, not certainly without sometimes having recourse to the counsels of competent authorities, but with a beautiful and joyful independence of any member of the family who may be too prone at times to attempt to domineer over the young couple. There should, of course, be no presumption, no narrow aloofness, but a serene and supple liberty of spirit; serene and supple humility.

In order to be able to practice the sanctity of their state in all the details of their life, they must understand their duty of leaning upon God. It will not be sufficient to link together their two wills; they must be determined to pray to obtain help from on High.

They must likewise have a certain concern, a legitimate concern, for physical charm, without, however, losing sight of the fact that beauty of soul is superior to beauty of body; so that if some day the physical attraction should diminish, they will not be less eager to remain together, but each will strive to find in the other the quality upon which profound union is established.

Both of them must love children. They must develop in themselves to the best of their ability the virtues necessary for parenthood, the courage to accept as many children as God wants them to have and the wisdom to rear them well–difficult virtues requiring strong souls.

Each must be possessed of a rich power of cordiality for the members of the other’s family. Both must resolve to take their in-laws and their household as they find them, and adopt as a principle for their contacts with them, It was not to share hates but to share love that I entered into your family.

Consequently, they must refuse to be drawn into family quarrels, seeking rather in all their actions to promote charity, union, and peace.

Even before their marriage, the young couple should decide to keep their expenses at a minimum, according to their situation, not with avarice or niggardliness, but with the desire to live in the gospel spirit of detachment from the goods of earth. Such judicious economy, which should of course be devoid of even the appearance of stinginess, will enable them to set aside something useful and necessary for their children. It will also enable them to relieve the misery around them.

It is to be assumed that both individuals contemplating marriage have the requisite health, since marriage has been created not only for mutual support but also to transmit life.

It is further to be assumed that each of the two has kept nothing of his past life hidden from the other, and that in view of this entire loyalty which is so desirable a trait in married couples, each has kept himself pure and refrained from dangerous experiences.

A PROPOSAL

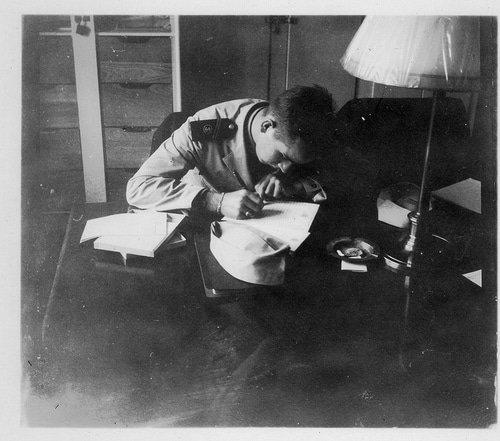

LOUIS PASTEUR came from a family of modest means. When he was twenty-six years old, his astonishing discovery in regard to crystals drew upon him the attention of scientists.

In 1849, he was named assistant professor in the University of Strasbourg. The rector of the university, Mr. Laurent, had three daughters. Fifteen days after Pasteur’s first visit, he asked for Marie in marriage. The young scientist felt that this young woman understood life as he did and wanted the same kind of life he sought–a life of simplicity, of work, and of goodness. He sent this letter to Mr. Laurent:

“Sir, a request of great significance for me and for your family will be addressed to you in a few days and I believe it my duty to give you the following information which can help to determine your acceptance or your refusal.

“My father is a tanner at Arbois, a little city in the Jura region.

My sisters keep house for my father since we had the sorrow of losing our mother last May. My family is in comfortable circumstances, but not wealthy. I do not evaluate what we own at more than ten thousand dollars. As for me, I decided long ago to leave my whole share to my sisters. I, then, have no fortune. All I possess is good health, a kind heart, and my position in the university.

“Two years ago I was graduated from l’Ecole Normale with the degree of agrege in the physical sciences. Eighteen months ago I received my doctorate, and I have presented some of my works to the Academy of Science where they were very well received, especially my last one. I have the pleasure of forwarding to you with this letter a very favorable report about this particular work of mine.

“That describes my present status. As for the future, all I can say is that unless I should undergo a complete change in my tastes, I shall devote myself to chemical research. It is my ambition to return to Paris when I have acquired a reputation through my work. Monsieur Biot has spoken to me several times to persuade me seriously to consider the Institute. In ten or fifteen years I shall perhaps be able to consider it seriously if I work assiduously. This dream is but wasted trouble; it is not that at all which makes me love science as science.”

Could a more modest, more completely sincere letter ever be sent by a young man in love?

And when he addressed himself to Marie he assured her with touching clumsiness that he was sure he could hardly be attractive for a young girl, but just let her have a little patience and she would learn his great love for her and he believed she would love him too, for “my memories tell me that when I have been very well known by persons, they have loved me.”

But great as was his love for Marie, his heart was divided:

Louis Pasteur loved science, he loved his crystals. He began to scruple about it, and finally wrote to his fiancée, asking her “not to be jealous if science took precedence over her in his life.”

She was not jealous. Madame Pasteur married not only the man but also his passion for science. Her love had that rare quality of knowing how to efface itself, and to manifest itself precisely by not manifesting itself at all at times. She was a worthy companion of this great man, of this great scientist, of this great heart.

No comments:

Post a Comment